|

Building up a diaspora from scratch (the conditions of emergence of process and collaboration in a global knowledge community) Alain Senteni, VCILT, University of Mauritius Abstract

INTRODUCTION

In the last quarter of the 20th century, open and distance learning (ODL) has emerged as a viable means of broadening educational access, while the massive provision of emerging open educational resources (OER) intends to provide the raw material out of which a new generation of educational systems will be built. However, while program design and provision of resources is critical, facilitating support for for teachers, teachers trainers, practitioners, learners and learning communities is vital in order to build on the foundations of ODL and achieve education and development goals. If we want innovative mindset, reflexive practices and collaborative learning to become effective, then there is a need for collegial support, support of institutions and organisational learning. As this became evident, ODL policies and approaches evolved from top-down technology-driven first generation to content-driven second generation which is participative to some extent. A third generation of technology-enhanced education (TEE) is now shyly emerging, mainly process-driven with a focus on grassroots level institutional-organisational learning and bottom-up empowerment. The purpose of this paper is to outiline the methodologies of this third generation of ODL, using intensively ICTs with an emphasis on the social component of learning and on the knowledge-creation process.

I. the evolution of Technology-Enhanced Education (TEE)

During the last decade, surveys showing the shortcomings of technology-driven approaches and the need for evolution opened the door to content-driven second generation TEE. In the year 2000, the report of the North American Congress on Latin America pointed out the failure of the “build the network and the users will follow” policy (NACLA Report on Americas, 2000) and insisted on the need for human-centered approaches supporting early adopters and pro-active practioners (Gray, Ryan & Coulon, 2004).

In July 2001, the UNESCO, in association with the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and WCET, the Western Cooperative for Educational Telecommunications, convened a forum on the Impact of Open Courseware (OCW) on Higher Education in Developing Countries. The OCW initiative of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a principal point of interest in the forum, consists of providing educational resources for free consultation and non-commercial usage by university and college faculty members as well as students, with permission to produce adapted versions. It also includes technology to support open access to and meaningful use of these resources.

The Open Educational Resources (OER) initiative, as the participants agreed to name it after the forum, is based on a philosophical view of knowledge as a collective social product to become a social property. However, the OER initiative regards the sharing of knowledge, mainly considered as a final product rather than a collaborative process. Although issues of contextualisation (i.e. re-processing) and knowledge-creation have been raised, it was never central to the sharing process but rather left at the initiative of local stakeholders and institutions. Implicitly, the conception/production engine remains the prerogative of international organisations and institutions from the North.

This is the case of the Open UK University, working with partners in Africa to make educational resources freely available under both the Teachers Education for Sub Saharian Africa (TESSA) and Open Door projects. During the initial phase of this initiative, the Open University will select and make available educational resources from all study levels from access to postgraduate and from a full range of subject themes: arts and history, business and management, health and lifestyle, languages, science and nature, society and technology. Learners will also be able to benefit from a range of study skills development material. This is as well the case of the African Virtual University (AVU) Capacity Enhancement Programme (ACEP), drawing lessons from the first phase of AVU technology-driven failure. The new ACEP places the AVU between second and third generations, mixing workshops and professional development programmes with the provision of open source contents.

II. The need for systemic Policies and Management in ODL

Simply opening access to knowledge is not sufficient to ensure that institutions in developing countries, which are presently mere users of open shared resources and courseware materials, would eventually become active players in a knowledge-production process. To attain this aim, there is an urgent need to formulate appropriate strategies. Placing the individual at the core of the underlying objectives, Calvert (2006) points out that the success of ODL programs depends on management policies and initiatives that are sensitive to the needs of learners (1), while also addressing wider acceptance in the academic community, thus requiring re-thinking of policies and practices that are the convention in traditional classroom-based education (2).

In the TEE lanscape, OER initiatives such as MIT-OCW, AVU, COL's Virtual University for Small States of the Commonwealth (VUSSC), TESSA and others have a strong impact on the whole educational system, generating contradictions and double-bind situations, in conflict with many existing institutional cultures and practices. If one looks at Calvert's recommandations, there is more often contradictions than complementarities between (1) and (2). Considered from a systemic perspective, educational institutions and systems obey a homeostatic logic whose role is to maintain the balance necessary to their stability and sustainability. Unfortunately, this homeostasis often acts as a barrier to innovation attempts that may well put into question this balance.

At the Arusha Biennal Meeting in 2001, the Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA) expressed its concerns about the lack of capacity shown in Africa for going to pilot to scale. Africa has benefited several pilot innovative projects sensitive to the needs of learners, without ever being able to scale-up and mainstream. Mainstreaming involves a number of processes such as moving from the margins and going to scale. More important, it is facilitated by such things as gaining official recognition and public acceptance, as well as having access to regular public funding and being an integral part of the examination system (Wright, 2003).

However, through its four pillars (capacity building, coordination, research and advocacy), the ADEA Working Group on Distance Education and Open Learning (WGDEOL) is geared towards sensitizing all stakeholders ranging from practitioners to policy-makers about the importance of ODL methodologies and related innovations in the educational scenario and to demonstrate the effectiveness of introducing ICTs in education in general and ODL in particular. This Working Group is also concerned with training local expertise, developing forums and mechanisms for the sharing of experiences, research, and good practices in ODL.

The WGDEOL is a good example of “Policy & Management Divide” whose consequences worsen the “Digital Divide”. While the link between working groups such as WGDEOL and local institutions should be quite strong and dynamic, the handing down of ODL policies defined at its international (macro) level suffers from a lack of commitment when it comes to grassroots implementation (micro level) and re-thinking of policies and practices that are the convention in traditional classroom-based education (meso level). In this respect, an important step has been taken by COL when involving in the decision making process of the VUSSC project, not only government stakeholders (interlocutors) but also implementors, in a holistic team.

Central commitment, ownership, responsibility and participation of the whole educational community in the full process of integrating ODL along with systematized capturing and sharing of knowledge on the upgrading process are at the centre of the scaling up process. Moving from pilot projects to mainstream nationwide scales of action requires implementors participation in the conception, development, financing, and upgrading of educational systems. This is maybe how ODL can become successful and sustainable. As Calvert again points out, the expanding and evolving use of ICT is certainly among the most significant changes in ODL, changing the division of labour in terms of the individuals required to design, develop, and deliver programs, and their roles in ODL. Additionally, there is an increasing emphasis on the social component of learning, which is an area often neglected, when the focus of policies and management have been on learning resources and quality control. III. ODL communities as “diasporas in progress”

A third generation of process-driven TEE is shyly emerging, with a focus on grassroots level institutional learning and empowerment. By implicitly making learners more responsible of their own learning process, ODL is the priviledged vehicle for a social conception of learning mixing identity (who are we becoming?) community (where do we belong?) meaning (what is our experience, our culture?) and practice (what are we doing ?), raising questions about how developing countries institutions and educators make sense of their new educational environment (What does it mean to teach in the new global knowledge environment?). Implicitly, the effective use and contextualisation of OER (i.e. re-processing) depends on existing educational systems in which team building, collaboration and sharing are new processes that cannot be taken for granted.

ODL approaches engage learners in a community building process, going from an individualistic vision of learning and knowledge to an instrument-mediated, socially distributed one. ODL policies, sustainability and expansion face the first chalenge of most distributed communities, which is to maintain informality and build trust across distance (the cement of all diasporas). The generalised use of ICT in ODL enables communities that span conventional boundaries of learning and doing, as well as space and time. Beyond ODL management, there is a need for knowledge enabling and knowledge creation involving shared understanding, shared values and shared belief systems and a few things at which diasporas are very good. There is also a need to share ideas and projects across different organisational units, to honor different national and organisational cultures and to build support allowing local variations, while linking to a larger structure.

According to (Wenger, Mc Dermott and Snyder, 2002), activities encompassing a common interest and ongoing learning through shared practice and shared knowledge are the starting point for building that trust. Then comes joint enterprise as understood and continually renegotiated by its members, and sustainability based on mutual engagement binding members together into a social entity. In this respect, ODL fosters the emergence of innovative learning and knowledge communities, considering working, learning and innovation as complementary forces for ensuring the long-term sustainability of these enterprising efforts.These communities are fundamentally self-organizing systems, structuring learning through the knowledge they develop at their core and through interactions at their boundaries. Expansion (i.e. growth and development) occurs through the learning that people do together (lifelong learning through work, learning by doing, experiential learning) and so does the social ODL entity, learning about itself, about its emerging capacity and its potential.

Innovative learning communities are empowered by the hierarchy, promote structured, activity-based, project-oriented learning, learn by doing, following pedagogical scenarios, and are steps towards sense-making, knowledge-creating, decision-making organisations.

IV. organisational learning as an engine of expansion

The work of the World Information Technology Forum Education Commission (WITFOR-EC) in the SADC region since 2005 - enhancing the competence of educators in integrating ICT in their work in pedagogically meaningful ways - is based on a five layers educational framework:

development and support of communities of practice,

collegial support offered to these communities using the Change Laboratory methodology,

collaborative set up of regional resource centres, using infrastructure, HR, tools and platforms available at VCILT and other centres in the region (BOCODOL, University of Botswana, etc),

institutional framework: online MSc Computer-Mediated Communication & Pedagogies, online MSc Interactive Learning Environments (VCILT),

showcase the work in progress thro' organisation of and participation to major international events : WITFOR 2005 (Botswana), 2007 (Ethiopia), ICOOL 2003 (Mauritius), 2005 (RSA), 2007 (Malaysia), eLearning Africa 2006 (Ethiopia).

IV.1. The change laboratory methodology

Change Laboratory is the name of a variety of developmental intervention and research methods, based on the principles of Developmental Work Research (DWR), a participatory research approach whose objective is to reveal the needs and possibilities for development in an activity - not in relation to a given standard or objective, but by jointly constructing the zone of proximal development of the activity.

Adapted to our specific purposes, the Change-Laboratory is a space either physical, conceptual or virtual, that offers a wide variety of instruments for analyzing disturbances and bottlenecks in the prevailing work practices and for constructing new models and tools for it are made available for the practitioners. It is also a forum for the cooperation between experts interventionist and local practitioners. During the lab sessions, practitioners take momentarily distance from their individual tasks. Their joint activity becomes the object of their collaborative inquiry and developmental experimentation.

In the Change Laboratories (Engestrom, Virkkunen et al., 1996), empowered practitioners:

question aspects of their present activity by jointly analyzing problematic situations in it,

analyze the systemic and historical causes of the identified problems,

reveal and model the systemic structure of the activity as well as the inner contradictions in the system that cause the problems,

transform the model representing the systemic structure of the activity in order to find a new form for the activity that would resolve in an expansive way the inner incompatibilities between its components,

find a new interpretation of the object/purpose of the activity and a new logic of organizing it,

begin to transform the practice by designing and implementing new tools and solutions.

IV.2. Example of a learning organisation

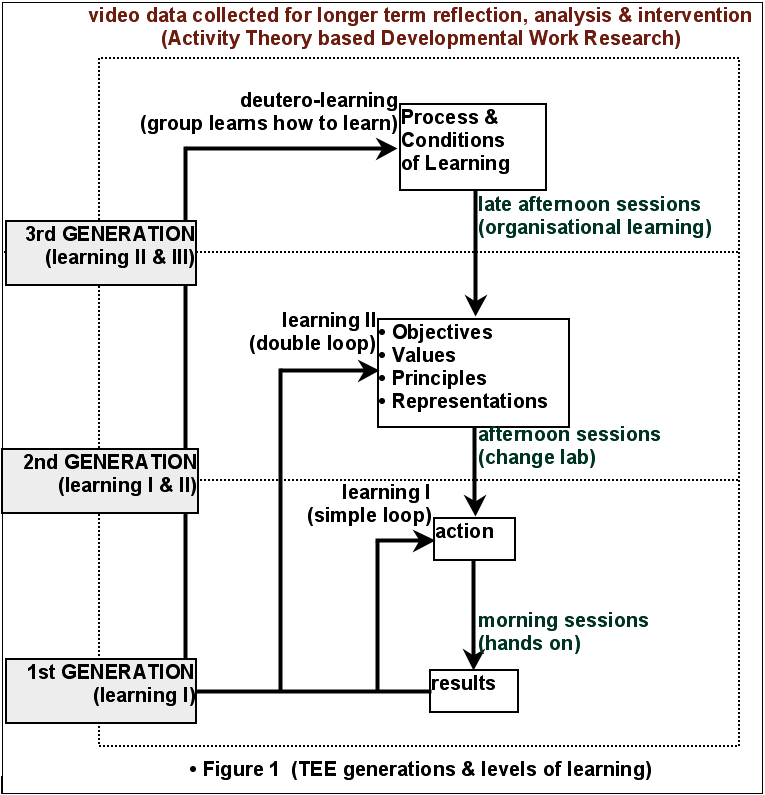

A one week wokshop organised by the Education Commission in November 2005 in Botswana is used as an example illustrating the overlall architecture of the project (Figure 1), fully scalable both timewise and groupwise. The same learning structure applies to longer period of time and to broader groups, teams, organisations, institutions. It regards the articulation of three conceptual layers at different scales :

Single-loop learning (I) occurs when errors are detected and corrected. The groups carries on with its present policies and goals. Single-loop learning can be equated to activities that add to the knowledge or specific competences of individuals, but it does not alter the fundamental nature of their group'ss (institution) activities.

Double-loop learning (II) occurs when, in addition to detection and correction of errors, the group is involved in the questioning and modification of existing norms, procedures, policies, and objectives of the institution. Learning II is the process by which an institution/organisation makes sense of its environment in ways that broaden the range of objectives it can pursue or the range of resources and actions available to it for processing these objectives.

Deutero Learning (III) is concerned with the why and how to change the group's assumptions and core beliefs.

On the long term, Learning II and III become expansive learning for it expands an organization's capacity (Engeström, 1987). Learning II and III are necessary to tackle the contradictions generated by the introduction of large scale OER initiatives (MIT-OCW, AVU, COL, TESSA, etc) in the global landscape of Technology-Enhanced Education (TEE), creating double-bind situations and conflicts with existing institutional cultures sand practices.

Example of double-bind situations

OER initiatives encourage CSCL and CSCW, based on team-building and considering a team (whole) as superior to the sum of its parts (individuals), but in the meantime:

- IPR is a concern, in a culture of competition,

- groupwork is not encouraged,

CONCLUSION

Etymologically, the term diaspora refers to a scattering of seeds, a good metaphor to talk about large scale ODL initiatives such as VUSSC, AVU, TESSA. In this context, OER appear as the scattered seeds from which knowledge and developement should emerge. However, if these seeds are essential, the whole process (development of ownership, evolution of mindsets, knowledge creation and expansive learning) depends on care, based on systemic approaches and developmental work methodologies.

Since its creation in 2001, VCILT focus on developmental intervention in environments facing economic, technological, cultural and social change, where innovation is a prerequisite for organisational survival. We seek to understand what fosters or inhibits collaborative learning while developing pragmatically methods and learning environments to facilitate its emergence. From a broader viewpoint, we aim at identifying how interlocking technical, institutional and educational structures can be designed to support the learning needed for adapting to rapid and unexpected demands from the environment (Engeström, 1987).

Based on methodologies to promote, trigger and support grass-root empowerment, development of strong ownership and effective emergence of innovative learning communities, our research expands at regional/international levels through the WITFOR-EC. While "enhancing competency for ICT integration in education" becomes a leitmotiv, we try to avoid duplication and maintain a strong identity based on 'developmental work approaches' regarding increased ownership, process-oriented, bottom-up methodologies. In this respect, the work in progress of the WITFOR-EC adds completude and systemic coherence to the lanscape of emerging large scale TEE initiatives in Africa (AVU, TESSA, TTISSA, COL, VUSSC, etc).

references

Calvert, J. (2006) “Achieving Development Goals - Foundations : Open and Distance Learning, Lessons and Issues”. Retrieved June 6 2006, from http://pcf4.dec.uwi.edu/overview.php Engestrom, Y. 1987. Learning by expanding. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit Oy. Engestrom, Y., Virkkunen, J., Helle, M., Pihlaja. J., Poikela, R. (1996). “The change laboratory as a tool for transforming work”. Lifelong Learning in Europe 2, 10 -17. Gray, D. E., Ryan, M., & Coulon, A. (2004). “The training of teachers and trainers: innovative practices, skills and competencies in the use of e-learning”. European Journal of Open and Distance Learning. Retrieved June 6 2006 from http://www.eurodl.org/materials/contrib/2004/Gray_Ryan_Coulon.htm. (NACLA Report on Americas, 2000) Virkkunen, J., & Kuutti, K. (2000). “Understanding organisational learning by focusing on activity systems”. Accounting Management and Information Technologies, 10, 291-319. Wenger, E., McDermott, R., Snyder W.M. (2002). Cultivating Communities of Practice, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 284 pages, ISBN 1-57851-330-8. Wright, D.C. (2003) ADEA Newsletter vol. 15, no.1, Jan-March 2003.

PCF4 (Senteni, 14 June 2006) - 4/5

Figures |