|

Digitally Assisted Diffusion of Innovations

Carole St. Laurent

Abstract

Development can be described as changing one’s actions to produce better results. Diffusion of innovations (DoI) research shows that communication factors are more important predictors of an innovation’s adoption than its efficacy (Nutley et al, 2002:19). Thus, how one shares knowledge is critical for improving people’s lives.

Audiovisual content is recalled four or five times better than material heard in a lecture, and nine times better than written material (Fraser and Villet 1994). In the diffusion approach, in which trainees train others, only a subset of the required knowledge reaches second-generation learners (in one case, 14%), and some of the information is distorted (Röling et al (1976:162)). Video offers first and second generations of learners the significant benefits of seeing and hearing 100% of a message during in-person training, and on demand later. It facilitates DoI best practices, such as using local change agents, opinion leaders, languages and content.

Whether the application is in the field of health, agriculture, education, or any other sector, increasing the effectiveness of information sharing through video offers exciting possibilities to expand the impact of development programs beyond the limitations of in-person training. A solar cooking case study in Nigeria will inform points of discussion.

Untitled Document

|

Content from audiovisual training materials is recalled

four or five times better than heard material, and nine times better than

read material.

(Fraser and Villet, 1994)

|

For several years, I have focused on how information and communication technologies

(ICTs) can practically benefit impoverished communities in rural Africa. While

working with telecentres in Nigeria, I noticed that text-based information in

CD-ROMs, websites and emails were under-utilized, even when the source was personally

known to the centre staff. This is not unique. In her research on the impact

of ICTs for development in Africa, Thione (2003, p.66) reports that even information

that communities request tends to remain unused. However, I noticed that the

youth at one telecentre watched the only available music video daily. I began

noticing the difference between my assumptions and preferences, as a member

of a text-based culture, versus those of people from a more oral culture. For

example, I used the Internet to search for information for the telecentre, and

copied text-based resources to the hard drive for offline viewing. The telecentre

staff did not review these resources. They primarily used the Internet for email,

which they typed slowly, even if they had taken a typing course. My touch-typing

skills surprised them. Also, they did not use their local languages on the computers.

Their software and much of their writing was in English, the official language,

although local languages are spoken almost exclusively. They had a Yoruba font

to support their accents, but had not installed or used it. Later, when I asked

for a written translation of an English video script, the project members referred

me to a Yoruba expert after hours of struggle; writing Yoruba is much more difficult

than speaking it. All of these experiences piqued my curiosity about the impact

of audiovisual mediums versus text as tools for informal adult education and

community development in Nigeria. This led to a joint solar cooking/video project

with these telecentres.

The impetus for the project began when the Ago-Are Information Centre and Fantsuam

Foundation asked for help learning how to solar cook. I sent them four-page

illustrated instructions for building and using a cardboard solar cooker, which

I had successfully implemented. My contacts were personal friends to whom I

provided email support. The necessary materials were available for under $5

US. The instructions were never fully implemented, although they confirmed their

interest in solar cooking and requested I continue supporting them.

This intrigued and sobered me. If literate, educated people did not successfully

use textual material to implement solar cooking, what would help them better?

To test whether a video would be more effective than text alone, we collaborated

on a solar cooking and video training project. While the project was too limited

to fully answer this question, the initial results were encouraging. New videographers

picked up camera and editing skills easily, and the amateur videos quite effectively

trained people how to solar cook.

If audiovisual materials indeed communicate more effectively than text, then

a great deal of development information could achieve better results if it was

delivered differently. Studies show that “we retain 10% of what we read,

20% of what we hear, 30% of what we see, 50% of what we hear and see, 70% of

what we say, and 90% of what we say and do” (Pike 1989, p.61, emphasis

mine). In development contexts, content from audiovisual training materials

is recalled four or five times better than heard material, and nine times better

than read material (Fraser and Villet 1994). Ninety-two per cent of primarily

illiterate farmers in Peru liked watching training videos because “it

was like ‘actually being in the field’” (Fraser and Villet

1994). Multimedia content is also more relevant than text for many developing

countries (Spence 2003, p.76). Centre de Services de Production Audiovisuelle

(CESPA) in Mali uses culturally adapted visual pedagogy principles developed

by Manuel Calvelo, and trains people to use educational videos for community

outreach.

Text, radio, and verbal presentations are prevalent ways of sharing development

information. If one retains only 10% of what one reads and 20% of what one hears,

impacts when using these mediums are significantly curtailed. Adding audiovisual

materials increases retention rates to 50%. When interactive training methods

are used to prompt the learners to say what they have learned, retention increases

to 70%. It reaches 90% when one explains the lesson out loud while practicing

it. This is particularly encouraging for “train the trainer” programs.

New technologies make creating and distributing multimedia content easier and

less costly, and reduce or remove obstacles posed by limited access to bandwidth,

electricity grids, and broadcast networks. In the North this is seen through

the multiplication of amateur videos, video blogs and podcasts. In the South,

it is time to take another look at development communications, their effectiveness,

and the potential of video to improve development impacts at the individual

and community level.

This paper uses the lens of diffusion of innovations (DOI) research to analyse

how development communications can support programs such as introducing solar

cooking. Strengths of DOI include its history, wide applicability (from marketing

to health interventions), breadth of communications activities (from building

awareness to persuasion to diffusion), and international relevance (Rogers 2003,

p.59, 93-94, 102-105). This paper proposes ways that diffusion of innovations

can be improved by the thoughtful incorporation of video. DOI also provides

a valuable model for designing the most effective video content. Therefore video

and DOI strengthen each other. This will be explored through the solar cooking

case study.

DIFFUSION OF INNOVATIONS

Everett Rogers, a pioneer in the field of diffusion of innovations, defines

DOI as the “process in which an innovation is communicated through certain

channels over time among the members of a social system” (2003, p. 5).

It has four component parts: “the innovation, communication channels,

time, and the social system” (Rogers 2003, p.11). Adoption or rejection

of the innovation occurs when an individual’s knowledge about it reduces

uncertainty to a tolerable level, allowing a decision to occur (Rogers 2003,

p.14). Rogers conceptualizes the innovation-decision process in five stages:

“(1) knowledge, (2) persuasion, (3) decision, (4) implementation, and

(5) confirmation” (2003, p.20).

The communication process about the innovation has different channels and objectives

at different points in the diffusion process. For example, mass media may be

involved in the introduction of the innovation to a population. When a respected

leader shares the information (called an “opinion leader” in DOI

literature), its impact increases. Since communities are not homogeneous, its

various sub-groups may have their own opinion leaders. Adoption is strengthened

when the appropriate opinion leader is used for the target audience (Rogers

2003, pp.26-27).

The promoter of the innovation, called the “change agent” (Rogers

2003, p.473), may discuss the innovation with people several times. The more

similar they are to their audiences, the more effective change agents are. Since

in fact they often differ substantially from their audiences, a more similar

communications aide is often used to reach target audiences (Rogers 2003, pp.19-20,

28).

The rate of adoption of an innovation varies significantly (Rogers 2003, p.20).

It is usually graphed as an S-curve, with the steepness of the slope indicating

the speed of adoption (Rogers 2003, p.23). The “take-off point”

occurs when 10-20% of the population have adopted an innovation (Rogers 2003,

p.11, 274), after which diffusion becomes self-sustaining. The time to take-off

can vary tremendously, and is generally measured in years (Rogers 2003, p.351).

Via email in August 2005, Pascale Dennery from Solar Cooker International shared

that it takes five years of active promotion to reach the take-off point for

solar cooking.

Professor Albert Bandura (Stanford University) provides important insights into

DOI via social learning theory, which states that people learn from others by

observing them in person or via media (Rogers 2003, p.341). Examples include

parents modeling for their children, teachers modeling for students, or children

imitating their favourite television characters. Even adults continue to learn

in this manner, for example, through television do-it-yourself programs.

Some weaknesses of DOI research are its bias towards successful diffusions (Rogers

2003, pp.106-107), under-emphasis of the rejection, discontinuance and re-invention

of innovations (Rogers 2003, p.107, 111), and the tendency to assign the blame

for rejecting a technology with the laggards, rather than with the system, change

agency, or developer of the innovation (Rogers 2003, pp.118-125). DOI is sometimes

criticized for helping the rich get richer, while leaving the poor no better

off (Rogers 2003, p.130). This can be avoided by forecasting the impact of an

intervention, targeting recipients from lower economic strata, and providing

enabling social conditions such as cooperatives and credit to give disadvantaged

people better access to innovations (Rogers 2003, p.134, 456-469).

Röling et al. (1976, p.162) provide another important critique of the DOI

model: the fact that information is distorted as it passes from the initial

recipients to the secondary audience. In one experiment, only 14% of the information

reached the second generation of learners. In another study, farmers received

only the new seeds introduced in a package of innovations, but no information

that was critical to successfully growing these seeds. In a third case, the

information reaching 25% of second-generation recipients was distorted (Röling

et al. 1976, p.162). These factors severely limit the ability of indirect learners

to implement an innovation. This contributes to increasing failure rates of

innovations due to lack of information, rather than lack of value.

Video’s Contributions to Diffusion of Innovations

How can video contribute to more effective diffusion of innovations? The low

and inaccurate knowledge transfer rates that Röling et al. quoted (1976,

p.162) are reason enough to incorporate video, which will consistently and accurately

communicate 100% of the message to all generations of learners. Also, seeing

is a more effective communication method than only reading or hearing (Fraser

and Villet 1994, Pike 1989, p.61). Videos, therefore, are valuable additions

to seminars, lectures, and print-based training materials. They can bridge geographical

distances, compress time, and illustrate the impacts of competing choices. Opinion

leaders, change agents and trainers can reach larger audiences on video than

they can in person. They can be shown at times that are convenient to the audience

and be watched multiple times. They can supplement in-person training programs,

or replace them when they are not feasible. They can be combined with other

technologies such as email, telephone, or SMS to provide remote support. This

increases the impact of training programs while decreasing their dissemination

costs.

SOLAR COOKING CASE STUDY

The goals for incorporating video into the solar cooking project were to expand

its geographical reach, to provide quality assurance for the diffusion efforts,

and to leave a knowledge resource behind with the trainees that was available

on-demand for unlimited use. Without incorporating video, the training would

have been limited to the two communities that I trained in person. As a source

of quality-assured content, the videos would overcome the risks of low rates

of knowledge transfer between first and later generations of learners (Röling

et al. 1976, p.162). They can virtually share messages from opinion leaders,

experts, or drama troupes that could not be made in person due to time, distance,

or budget. They can be reviewed when experiencing difficulties, or when one

wishes to incrementally adopt new skills (e.g., first learning how to solar

cook food, then adopting solar water pasteurization). Combining them with in-person

interaction and demonstrations strengthens both training methods. Video can

also be used interactively during the diffusion process itself, to capture new

trainees’ efforts, to help them see their successes and mistakes more

clearly, or to show the benefits and challenges others faced when adopting the

innovation. The best additional footage could be incorporated into future training

programs. Video is also a very powerful communication method to deliver questions

and answers between a trainer and trainees, allowing the trainer support more

people than s/he could in person. Video is a valuable communications tool between

extension agents, farmers, and agricultural institutions, where better information

can improve farm yields and influence future agricultural research (Walker 1999).

They can be delivered physically, electronically, or both, effecting a local,

regional or global impact.

What did our solar cooking video project demonstrate? After using the videos

we created in Nigeria during training workshops, I am convinced that they do

communicate more effectively than print. Everyone who saw the solar cooking

video wanted to try solar cooking, although most had no prior knowledge of it.

However, the project leaders did not thoroughly review the printed training

materials I brought, nor photocopy them. While time and financial constraints

may have influenced this decision, they could have been overcome by asking volunteers

to scan the materials. Print resources would have been even less effective for

those project beneficiaries who had limited education, or who were functionally

illiterate in English, the language of the training materials. In contrast,

even passers-by stopped to watch the videos, which were in local languages.

Video is a very popular medium in Nigeria. Both project communities have viable

video rental stores, although a small proportion of the population owns TVs

and VCRs. Ago-Are Information Centre’s most popular business is selling

tickets to watch televised soccer games. Showing educational videos after the

games was one of the outreach plans we discussed.

To evaluate the video’s impact, we administered baseline questionnaires

to test participants’ familiarity with solar cooking. Except for those

who had seen someone solar cooking on the premises, none of the participants

had any prior knowledge of solar cooking, and they reported their knowledge

as “none” or “a little.” We showed the video, then administered

follow-up questionnaires to gauge the knowledge learned from the video. Next,

we tested the participants’ practical solar cooking skills by asking them

to demonstrate the use of three types of solar cookers. Finally, we demonstrated

solar cooking in person, and cooked a meal together.

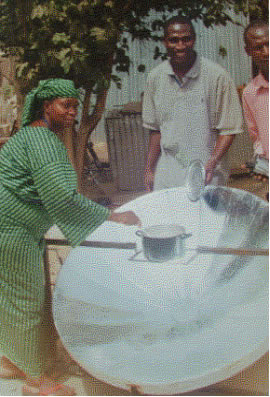

Everyone could successfully demonstrate how to solar cook in the simple box

cooker after watching the video. Only 28% of the trainees understood how to

use the more complicated parabolic cooker based on the video alone, and no one’s

first try at aiming the parabolic stove was completely accurate. Ideas to improve

future training results include interspersing watching the video with implementing

the steps one by one, and improving the video content. For example, it could

show people attempting to aim the stoves. The narrator could ask the viewers

to identify any mistakes made, either individually or in groups, and instruct

the viewers to pause the video while they discussed this. The subsequent footage

would provide the correct answers. The videos should also contain self-evaluation

indicators for the trainees to test their implementation skills (e.g., showing

onions frying on the parabolic cooker, and encouraging trainees to adjust the

cooker until they achieved enough heat to do the same).

A home economics teacher and a nurse were the participants who most quickly

and thoroughly grasped the principles and skills of solar cooking. They could

capably experiment with solar stove designs and recipes, and their teaching

and public health experience would make them excellent trainers. I believe they

could have successfully learned solar cooking based on video training alone.

Most other participants, who were primarily housewives or market vendors, needed

more support and in-person demonstrations to successfully solar cook. While

the training methodology could be improved, adopting a new cooking method is

more complex than just learning the skills. One needs to be persuaded it is

valuable, invest in the solar cooker, persevere in practicing the skills and

perfecting new recipes, and build the various steps of solar cooking into the

household routine. Therefore, I recommend that videos first be used to “train

the trainers,” whether this is through distance education or in-person

training. These trainers can then show others how to solar cook with the support

of the video for 100% knowledge transfer, and to show time-compressed demonstrations

of solar cooking and multiple recipes (which would take hours in person, and

which busy women and men do not have time for at a workshop). Sharing supporting

information is important, like how quickly the cooker pays for itself, the health

and workload benefits, opportunities for small businesses, etc.

Fully understanding the video’s success was curtailed in some respects

by project limitations. For example, we could not afford to buy prefabricated

stoves. Instead, we sought to train entrepreneurs how to make solar cookers

for sale to the community. We ran three construction workshops, but no trainees

made cookers to sell while I was there, and no families made their own cookers.

Since no one adopted solar cooking at home, we could not compare the effectiveness

of interpersonal knowledge transfer with video-based knowledge transfer to second-generation

learners.

Inexperienced volunteers developed the video. They quickly grasped videotaping

and editing skills, and required guidance in designing the storyboards, timelines,

and content. Videographers who made VHS or digital videos for weddings or government

functions had the best video skills, and would be the natural choice for video

“train the trainer” programs.

CONCLUSION

Easier and less expensive technologies make it more feasible for people to be

digital content creators today than ever before. The content can remain local

to one computer, one community centre, shared with small numbers via email or

online groups, or with the world via the Internet. Video podcasts with creative

commons licences offer one way of sharing content.

Colle (2005) suggests that universities and research centres link with telecentres

to develop and distribute local content to communities. Aina (2006) recommends

linkages between libraries, extension agents, and farmers, and the repackaging

of print-based materials into accessible formats for illiterate farmers, including

video.

In 2005, the Ago-Are Information Centre and the International Institute of Tropical

Agriculture (IITA) implemented a joint project to help farmers interact with

researchers via email. Unedited video would be even better for showing crop

problems and interventions. It is more accessible to illiterate farmers, and

allows more “virtual” discussions with an extension agent than are

possible in person. The videos could contribute to training resources for IITA

to share with other research institutions through online and offline methods.

Clearly, a video that successfully communicates knowledge is a static tool until

somebody watches it, implements it, and promotes it. That is why CESPA trains

its trainers to effectively use video educational materials. In the book “Participatory

Video,” Shirley White (2003, pp.392-397) shares valuable recommendations

about using video for development, including evolving telecentres into Community

Communication Centres that serve as hubs for local development. Investing in

this vision would have a greater impact at the telecentres I have worked with

than investing in more computers or bandwidth would.

If modern audiovisual materials are indeed more effective educational materials

than text, a wonderful opportunity exists to increase the impact of existing

development knowledge by supplementing text-based communications with multimedia

communications. Audiovisual training materials allow professional knowledge

producers such as development organizations and grassroots organizations such

as telecentres make important information more accessible to the neediest audiences.

Development libraries should provide more multimedia materials, accept content

created in the field, and validate them for accuracy. They should be indexed

by topic, audience, format, and language, and peer-ranked for effectiveness,

similarly to how software is ranked on www.download.com. They can be shared

online, via physical media, or broadcast. They are accessible to illiterate

people, to those whose learning styles favour demonstration and oral communication

over reading, and to women, who suffer from the highest rates of poverty and

the lowest rates of education. In all sectors and regions, the potential to

increase information retention from 10% to 50% simply by changing its medium

is very compelling. The training needs surrounding HIV/AIDS provide good examples.

Whether to teach prevention methods or to help AIDS orphans gain life skills,

videos may be more than just alternatives to printed materials in these cases

– they may be important supplements to severely limited human resources.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH QUESTIONS FOR THE USE OF VIDEO

FOR DEVELOPMENT

The experience of implementing the solar cooking and video training project

provided some valuable lessons that may be helpful for future projects, and

questions for future research. These are shared below. For more information

about the project, please visit www.fluidITsolutions.com.

CONTENT AND FORMAT

Quality Assurance: Evaluate Practical Skills Practically

Testing whether a video communicates the desired information effectively is

very important to fine-tuning it. If the video seeks to impart practical skills,

it should be evaluated by asking viewers to provide hands-on demonstrations,

because they may miscalculate their level of learning during an interview or

questionnaire. In the solar cooking project, more people said they were ready

to solar cook on the questionnaires than could properly apply the techniques

in person.

Self-Evaluation Content In Lieu Of An In-Person Trainer

When the finished video is used for distance learning situations in which no

trainer is available in person, participants must be able to evaluate their

learning themselves. It is helpful to include content that allows people to

confirm that they have applied the lessons correctly. For solar cooking, one

could describe the expected shadows under the solar cookers, how long certain

foods take to cook under various weather and seasonal conditions, and show foods

frying in the parabolic solar cooker.

Consider Various Audiences: Novice, Beginner, Intermediate and Advanced

Consider the needs of viewers at various stages of implementation of the lessons

on the video. Often a video assumes the audience has never seen it before. When

a video will be used to train people in practical skills, especially by self-directed

learning, it should encompass the learner’s needs throughout the learning

cycle. What are the needs of learners who are novices, beginners, intermediate,

advanced, or those who could become trainers of others? A novice needs full

information, but delivered in manageable chunks. A beginner would benefit from

a summary of the key lessons that can quickly reviewed. A troubleshooting section

might be helpful for those who are struggling with some aspects of implementation.

An intermediate learner is ready for more advanced techniques – in solar

cooking, this might be new recipes, or the principles needed to experiment with

one’s own recipes. An advanced solar cooker might be ready for baking.

And a “train the trainer” section would support people who wish

to share the lessons they learned through the video with others in person. For

example, Centre de Services de Production Audiovisuelle (CESPA) in Mali produces

videos, and also trains people how to use them effectively for community outreach.

For complex topics, perhaps a video series would be best.

Maximizing Recall And Practice

Encouraging viewers to think through and/or vocalize the principles being taught

may lead to better recall and practice. For example, one could show examples

of solar cooking, and ask the viewers to pause the video, then discuss whether

the stoves were used correctly or not. Then they could continue watching the

video to hear the answer and explanation for it. Include enough examples to

review the most common mistakes revealed during the video evaluation step.

Reinforcing Content Through Creative Interaction And Pedagogy

DVDs and online multimedia programs make it easy to separate content into questions

and answers, or into chapters. Videos presented in other formats can be manually

stopped and restarted. Be creative with the interactive use of video training

materials. A video can introduce a scenario, be paused for group discussions,

be interspersed with hands-on practice, or ask a question and be paused for

people to hold discussions in pairs or groups, or come to their own conclusions.

Video use should be incorporated into educational best practices, going beyond

the broadcast model of simply showing a video from start to finish, without

interaction. This type of interactivity is especially well supported by computer

and web-based training.

Languages and Translation

To use the same footage for videos in different languages, it is helpful to

separate the action shots from the explanation shots. Since explanations take

different lengths of time in different languages, timing voiceovers to action

shots is difficult. It is easier to do a voiceover of someone explaining something,

when you can truncate some footage or extend it by inserting images, as needed.

One can even videotape someone explaining the action shots in the second language,

and intersperse this footage with the original action shots. This methodology

would be better than voiceovers, based on diffusion of innovations research

that states that change agents with similar backgrounds and languages exert

the most influence on audiences.

ONGOING SUPPORT

Support is easiest to offer in person, but it can also be provided remotely.

The intention with the solar cooking project was to develop videos that could

be used as distance learning materials by people without access to in-person

training. ICTs offer various means of providing this support, including email,

voice over IP (VOIP), online instant messaging, online groups, SMS text messages,

or telephone. In this project, we tested weblogs and email groups as potential

support mediums for the geographically dispersed participants. People preferred

the format of weblogs, but wanted the functionality of online groups –

particularly because one can participate in the group simply via email. Therefore

we chose a solar cooking Yahoo! Group as our method of ongoing interaction.

Where possible, a community resource person can participate in the online discussions

and relay messages back and forth to their communities in person. To broaden

accessibility even further, the interactions on the email group can be converted

into audiovisual materials and periodically delivered to participating communities,

so that the information is shared beyond project members whose literacy, language

skills, and Internet access allow them to participate online.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Amateur Versus Professional Videos

It would be worthwhile to compare the impact of a professional-looking, edited

video with a simple video that uses in-camera edits, or no edits at all. If

a simple video is equally or almost as effective as a professional video, then

almost anyone can be trained to use a basic camera for educational purposes.

The video content would need superior planning and storyboarding, however, because

editing it later would not be possible in this case. Simple videos will likely

be effective, based on the strong history of participatory video. For example,

Ochuko Ojidoh from the Community Life Project in Nigeria told me that “rough

cut” videos enhance their work. They videotape meetings, and playback

the video immediately to remind people of the discussion, make the issues clearer,

and help them see gaps in the discussion or plans. New video trainees also quickly

gain the skills needed to produce their own videos. Trainees from the solar

cooking project gained the skills to create a water and sanitation video in

a three-day video production workshop. These examples show how valuably video

can contribute to community feedback, participation, and awareness building.

Comparing Educational Materials

This research project explored the question as to whether a video would be a

more successful training medium than Solar Cooking International’s printed

training materials. It would be interesting to formally evaluate this. The research

criteria could include how much information was remembered immediately after

the training, and after a period of time; how much information reaches the second

generation of learners, how accurate the information is, and the adoption rates

of solar cooking. It will be important to isolate the impact of the training

mediums from other factors that might influence the adoption of solar cooking.

Impact Of Videos On Rates Of Adoption Or Rejection Of An Innovation

To successfully introduce solar cooking to a new region takes approximately

five years, according to Solar Cooking International. It would be interesting

to research whether the use of video accelerates the decision-making step in

the diffusion of innovations process (Rogers 2003:20), or if it reduces the

amount of time required to achieve the “take-off point” of sustainable

diffusion.

REFERENCES

Aina, L. O. (2006), Information Provision to Farmers in Africa: The Library-Extension

Service Linkage [Online], The International Federation of Library Associations

and Institutions (IFLA), The Hague. Available from: <http://www.ifla.org/IV/ifla72/papers/103-Aina-en.pdf>

[6 August 2006]

Colle, R. (2005), ‘Building ICT4D capacity in and by African universities’,

International Journal of Education and Development using ICT, [Online],

vol.1, no.1. Available from: <http://ijedict.dec.uwi.edu/viewarticle.php?id=13>

[9 August 2005]

Fraser, C., & Villet, J. (1994), Communication, a key to human development

[Online], FAO, Rome. Available from: <http://www.fao.org/documents/show_cdr.asp?url_file=/docrep/t1815e/t1815e01.htm>

[5 December 2004]

Pike, R. W. (1989), Creative Training Techniques Handbook: Tips, Tactics,

and How-To’s for delivering Effective Training, Lakewood Books, Minneapolis.

Rogers, E. (2003), Diffusion of Innovations, 5th Edition, Free Press, New York.

Röling, N., Ascroft, J., & Wa Chege, F. (1976), “The Diffusion

of Innovations and the Issue of Equity in Rural Development”, Communication

Research, vol. 3, no.2, pp.155-171.

Spence, R. (2003), Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs) for Poverty

Reduction: When, Where and How? [Online]. IDRC, Ottawa. Available from: <http://web.idrc.ca/uploads/user-S/10618469203RS_ICT-Pov_18_July.pdf>

[12 August 2005]

Thione, R. M. (2003), Information and Communication Technologies for Development

in Africa, Volume 1: Opportunities and Challenges for Community Development,

IDRC, Ottawa, and Council for the Development of Social Science Research

in Africa, Dakar.

Walker, D. (1999), Technology in the Hands of the Extension Officers -

Agricultural Extension in Jamaica and Ghana, Commonwealth of Learning,

Vancouver. Available from: <http://ictupdate.cta.int/index.php/filemanager/download/38/COL_Jamaica.pdf>

[29 July 2006]

White, S. A. (2003), ‘Video Kaleidoscope: A World’s Eye View

of Video Power’, in Participatory Video: Images that Transform and Empower,

ed. S. A. White, Sage Publications, New Delhi, pp. 360-398.

Figures

Figure 1: Rashid Adesiyan checking water in CooKit Panel Solar Cooker, Ago-Are, Nigeria

Figure 2: Box Solar Cooker with Glass Lid, Ago-Are, Nigeria (with Rukayat Adewumi, front, and Grace, back)

Figure 3: Parabolic Solar Cooker, BayanLoco, Nigeria (left to right: Maria Ajayi, Pastor David Adesokan, Ezekiel Kyari)

Figure 4: Deborah Akinwande and Gloria Ayuba videotaping solar cooking, BayanLoco, Nigeria

|

|

Learn more

about this

publishing

project...

|

|