|

More than blended learning: lessons learnt in postgraduate health studies

Sharon Huttly

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University of London

Susan Horrill

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University of London Anne Tholen

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University of London

Abstract

In the late 1990s the LSHTM launched postgraduate distance learning courses alongside its long-established face-to-face courses. Now a flourishing programme with students from over 100 countries, the distance learning initiative has realised a key aim of widening participation through alternative study opportunities. This paper will reflect on the experiences of offering the two primary study modes in parallel and on the developments which have occurred in each through lessons learnt from the other. As expected, over time, overlap of the two modes has occurred with respect to student learning opportunities, further enhancing flexibility of study options and helping to address diversity of learner needs. However, the paper will also consider other dimensions in which such blending has occurred such as course management, quality assurance and enhancement, student support and learning resources. Quantitative and qualitative data from practice-based research and case study examples will be used to illustrate these multiple dimensions of blending. The paper will conclude with the implications of these findings for distance learning in the field of postgraduate health studies.

More than blended learning: lessons learnt in postgraduate health education

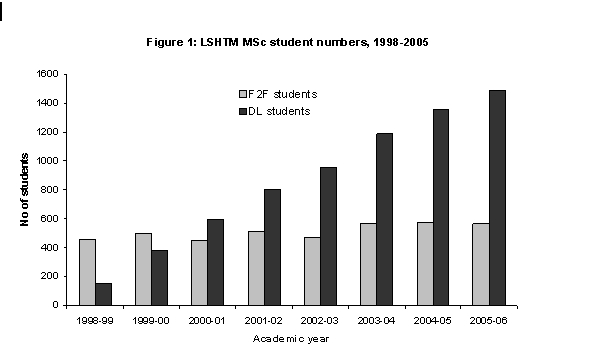

The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), a self-governing postgraduate college of the federal University of London, opened its doors in 1899 with eight staff and eleven students. After many years of successfully running face-to-face (F2F) courses, in 1998 it launched its first distance learning (DL) courses. The most immediate effect of this shift in teaching mode was a substantial and continuing rise in student numbers (Figure 1). As staff attitudes changed to embrace this new mode, the DL programme guided significant development in terms of the management and administration of teaching, enhancing not only the DL programme but also the F2F courses. This paper reflects on our experiences of offering dual-mode education, particularly with respect to ensuring parity between study modes, and on the resulting developments which have occurred in each mode - for learning and teaching, and other dimensions such as quality assurance and course management. We begin with a brief description of the LSHTM Masters programme.

The programme is wide-ranging and multidisciplinary with over 20 MSc courses in international public health and tropical medicine, attracting students from over 100 countries. Approximately two thirds are female and the average age is over 30 years. Both the DL and F2F courses are modular in structure with compulsory and elective modules, allowing students to tailor the MSc to their career needs. Table 1 summarises some key descriptors of the two modes.

Table 1. Description of the MSc programme

|

|

|

|

|

Five. Vary in extent to which they “map” onto a F2F course.

|

|

1 year full-time or 2 years part-time. Most students are full-time, taking a break from professional activities

|

Two to five years, usually studying whilst working

|

|

Scheduled modules and deadlines throughout the study year

|

Few deadlines, students plan personal schedules and study at their convenience.

|

|

F2F teaching supported by extensive written materials, students also expected to seek out additional resources e.g. via the library

|

Specially written learning packages, textbooks, journal articles. Computer Assisted Learning only used where it offers pedagogic advantage. Students encouraged to use local resources where available.

|

|

In-course work; exams; dissertation; (some, practical exam)

|

In-course work; exams sat at University of London-accredited examination centres worldwide; (some, dissertation)

|

Student-student and student-staff interaction

|

Primarily F2F with occasional on-line

|

Primarily on-line via web-based conferencing system (also usable via email)

|

The F2F programme is run entirely by the LSHTM whilst responsibility for running the DL programme is shared with the University of London's External Programme which has delivered DL courses for almost 150 years. LSHTM sets, delivers and monitors the academic content and integrity of the courses, the External Programme manages core administrative functions such as student admissions, dispatch of study materials, and coordination of examination arrangements. This shared responsibility adds some administrative complexity but has also led to quality enhancement. For example, the External Programme's extensive experience of offering study by DL worldwide informed key aspects of the programme's design which were different from F2F delivery.

We now present some lessons learnt from our experiences of offering the two study modes, firstly with respect to the learning and teaching, and secondly for other aspects of programme delivery. We refer to this as a process of blending, capitalising on the term of `blended learning' although recognising that this has varied interpretations in the education sector.

Blending - Teaching and Learning

Blending of teaching occurred from the very start of DL course development, the courses being aimed as independent study opportunities but with their design strongly influenced by the F2F programme. The practice of supporting F2F teaching with extensive materials written for an international audience facilitated development of DL materials based on similar content. There was considerable involvement of F2F teaching staff at the design stage, as authors or advisers, which was important for the DL courses to be similar not only in content but also philosophy, tone and structure. These similarities have assisted tutoring staff who support students in both modes and have probably contributed to the success of mixed mode study (see below), i.e. the “look and feel” of the course content is similar even though the learning style is very different. Another area of design overlap was in assessment - with substantial experience of using varied forms of assessment at postgraduate level, the DL courses also attempted to replicate this approach by including different types of assessment tasks. Again this facilitated the later mixed mode plans.

This early-stage blending worked both ways, however. Staff reported using the DL design experience and materials to update their F2F courses and to re-evaluate and extend their conceptualisation of how students learn. Materials in one mode have also been used to supplement teaching in the other, for example DL materials serving as exam revision aids and major F2F expert seminars being made accessible to DL students via the Internet. More explicit integration has been slower but is now occurring.

These examples essentially leave students classified as wholly DL or F2F learners. More recently, explicit mixing of the study modes has been piloted. Although the courses had many similarities, there were differences in their delivery, requirements and regulations which meant that enabling students to mix modes needed careful planning. The first pilot of mixing involved F2F students being permitted to undertake specific elements of their studies by DL - taking1-2 modules entirely by DL, entering into the DL framework of academic and administrative support, and not attending parallel F2F classes. Prior to implementation, an email survey of current F2F students was conducted. Over 80 replies were received from 500 students emailed, voicing strong support for the proposal. Most stated that they had never studied by DL so it was perhaps unsurprising that they indicated a strong preference for F2F learning wherever possible. However they recognised, as the staff had predicted, that taking some modules by DL might be particularly attractive to part-time students or where F2F timetabling clashes occurred. This feedback helped plan the supporting information for the pilot - for example, addressing the lack of experience with studying by DL.

The pattern of mixed mode study over three years has largely confirmed the anticipated picture. The proportion of F2F students who wish to substitute some of their studies with DL is low (<5%). Dispersed across a large number of modules, obtaining quantitative feedback on the student experience has proven challenging. However, despite DL being new to most, the experience is widely reported as positive, complementary to their F2F learning (which still forms the majority of their studies) and enhancing study opportunities, especially for non-UK students.

The reverse form of mixed mode - DL students attending F2F courses in London - was started in 2005-06. The extra financial and other costs are predicted to limit take-up and in its first year only two students participated. Both reported positive benefits of their experience, however more data are needed before firm conclusions can be reached.

Blending - Beyond Learning and Teaching

A range of quality assurance methods governing student support, assessment, evaluation and learning resources help ensure that the DL courses are maintained at a high standard equivalent to that of the F2F courses. These include ensuring similar learning outcomes between courses of the same discipline, while providing consistent learning and teaching opportunities between all LSHTM courses. We outline below specific examples in which we addressed such quality assurance issues while running the dual modes of study in parallel.

Blending - Course Management

A key mechanism for monitoring this equivalence process is the management structure. In general, the aim was to integrate the DL courses into the existing course management system from the beginning. Firstly, each MSc course has its own Course Committee which reports to a Departmental Teaching Committee (of which there are 3) where courses of similar disciplines are brought together. This is a valuable forum in which to exchange ideas and enables issues such as subject content to be looked at across the courses. Finally, all courses are represented at an institution-wide Committee where issues common to all courses such as assessment regulations are considered.

In general, this integration of DL courses into the committee structure has proven useful to staff, for example in adopting similar approaches to course review and in keeping abreast of course developments. Initially, the practice of F2F MSc Course Committees including student representatives was considered difficult by staff to replicate for the DL courses. However, students' enthusiasm to overcome the difficulties led to a mechanism which combines DL students based in London acting as representatives who use web-conferencing facilities to gather issues and to feed back. Inclusion in the student representatives system has helped DL students better understand what F2F students experience and vice versa, and was recently highlighted in an external audit as an example of good practice for wider dissemination.

In addition to the committee structures, each MSc has a Board of Examiners responsible for ensuring assessment procedures are followed and for determining the final degree results, thereby playing an important part in maintaining the academic standard of the awards. The DL and F2F Boards in the same subject area have some overlap of membership. This overlap is not only a critical mechanism for ensuring the equivalence of academic standards between the modes of study but has helped dispel much of the initial scepticism among academic staff about the standards that could be achieved by DL studying.

On the whole the committee and management structures integrate the two modes. The specific needs of DL, and the tendency for F2F matters to dominate committee agendas, have also given rise to a DL-specific forum which brings together key DL personnel from across the three academic Departments. Linked to the main integrated structure, this forum works with, rather than in isolation from, the key decision-making bodies but it provides a mechanism to address DL-specific matters more effectively.

Blending - Student Feedback

A key contributor to the LSHTM's quality assurance processes is student feedback on their study experiences. In broad terms, feedback from F2F students is obtained formally through module and course reviews, together with evaluations of key student support services, as well as informally. Initially, replication of the formal mechanisms were attempted with the DL students, however response rates were very low. Alternative approaches, for example through electronic submission which maintained student anonymity, had to be introduced. Replication of less formal mechanisms was attempted through the web-based conference system. With appropriate encouragement from staff, DL students have used this mechanism although there is a tendency to raise issues in this “public forum” which F2F students would more usually raise on a one-to-one basis. In summary, the principle of attaching importance to the collection and use of student feedback has been applied to both modes although more flexibility and adaptation of the F2F approach was needed than initially thought.

Blending - Staffing Support

The introduction of DL courses was intended to increase student recruitment and thus, necessarily, required additional teaching resources. In the early stages, an assumption that F2F teaching was more challenging led to a disproportionate number of less experienced staff teaching on DL. It was quickly recognised that this was a misplaced assumption, for example the written and permanent record of all discussions on the web-based conference board was very intimidating and challenging for these staff. This lesson, however, helped raise the status of DL by recognising its particular delivery challenges.

Three key changes in staffing support have occurred:

Staff based overseas: they are unable to make a significant contribution to the F2F programme, under-utilising a valuable resource as well as denying academics teaching experience needed for their career development. DL has created opportunities for these staff and they now make a valuable contribution to the tutor workload and bring their fieldwork experience to the DL students. Maintaining teaching experience in this way means also that, on return from overseas, staff are better equipped to resume F2F teaching.

Use of `external' tutors: the increase in staff needed to provide academic support to students necessitated the employment of staff from outside LSHTM. This releases pressure on internal staff with sometimes the simpler tutor tasks being performed by external tutors allowing more complex tasks which need internal access, such as course updates, to be undertaken by internal staff. Based anywhere, this change has provided a mechanism to involve alumni who can keep up-to-date with their subject, a problem faced by many F2F students returning to resource-constrained environments. It has also begun to make direct monitoring of staff's teaching more acceptable - initially viewed as necessary for external staff but becoming seen as constructive development for all.

Estimating teaching workload: the nature of the DL work is quite different from that of F2F, yet in both modes of study there are many different teaching tasks, each taking up varying amounts of time and expertise. The introduction of DL highlighted the need to measure (in time) the specific teaching tasks in order to ensure an equitable workload was assigned to teaching staff, regardless of the mode of study or teaching task. A system of teaching allocation is now in place measuring teaching in both terms of quantity and teaching tasks.

Blending - Staff Training

The staff development programme was expanded to accommodate DL-specific training, however many elements are non-specific to DL so that staff who only teach via one mode are likely to encounter staff only teaching the other mode in these forums. Training is broad, including pedagogic aspects of course design, through assessment techniques, to equality and diversity awareness. The exchange of experiences from the different modes of study in relation to common issues, such as accessibility of learning materials, has enriched debates and contributed to raising the profile of DL among staff. The DL-specific training has also led to development of the training programme overall - an on-line training course developed for DL tutors, both to help replicate the student experience of being a distance learner and to make the training more accessible to tutors based away from London, was very successful. The on-line delivery mode is now being adopted for other training elements, such as in health and safety, to increase their accessibility to all staff.

Blending - Learning Support

Other learning support has been relatively straightforward to blend and make equivalent opportunities available. For example, web-links to resources to help general study skills development such as essay writing and access to careers advice are available to DL and F2F students. Administrative staff play a crucial role in supporting students, providing one of the key threads of continuity as students progress through a modular study system. Although the arrangements vary to deliver this support and are operated separately for DL and F2F, it is significantly valued by all students.

Our extensive experience of supporting international F2F students, with diverse educational backgrounds and professional experiences, meant that the value of peer exchange and the potential gains from the formation of strong student communities, was recognised. Creating the opportunity for peer exchange was initially, however, only built into one DL course which required students to have email and preferably Internet access. That experience reinforced the importance of this feature and peer exchange through a web-based conference system is now incorporated into all courses, facilitated by rapidly-growing Internet availability.

LSHTM's move into dual mode provision surpassed its expectations. Success in reaching out to new audiences around the world has encouraged us to develop additional courses to meet a growing demand for postgraduate studies in this field. The materials created are also being adapted in partnerships with Southern institutions to help develop new educational opportunities there. Many lessons have been learnt along the way, only some of which are illustrated here.

A recent review article by Hope (Hope, 2006) summarises factors for success in dual mode institutions to develop a best practice framework which covers four areas - organisational culture; programme planning and development; teaching, learning and student support; planning and management of resources. The framework provides some useful guiding principles, although several would appear not to be specific to dual mode institutions. Our experience with dual mode provision supports the idea of a changing paradigm of how learning is supported/teaching conducted that has implications for organisation and management and we add the following observations to Hope's framework:

Organisational culture needs time to evolve. In new terrain, staff need to learn from direct experience to believe in and endorse parity between modes.

Concerns about adding a `new mode' to an existing one can promote healthy debate about, and focus attention on, matters which previously are largely assumed, such as tutor workloads, costs of delivery, monitoring quality of staff's teaching, many of which can contribute to quality enhancement in teaching and its management.

Integration of structures and systems is an important contributor to ensure parity of student experiences and academic standards, however there are mode-specific needs which may be better served by complementary mode-specific solutions.

Rapid IT developments can assist in academic content delivery where appropriate but can be at least as important for other aspects of learner support and quality assurance such as expansion of a tutor network, collection of student feedback and creation of peer learning environments.

Closer blending of provision, rather than separate dual mode, strengthens the need for Hope's principles to apply. Our mixed mode pilots have helped increase flexibility of study opportunity but highlighted some not insignificant differences to address. Some of these differences were inevitable whilst others might have been minimised if more integrated planning had taken place when the DL courses were established. In pursuing the flexible study agenda, we see further IT development as a key contributor but it can better fulfil its potential for extending the possibilities for advanced study in otherwise resource-constrained environments if it is seen as more than just a content-delivery tool.

Hope, A. (2006), Factors for success in dual mode institutions. Available at

Major points as a PowerPoint presentation

From single to dual mode provision

Blending - beyond blended learning

Factors for success and concluding remarks

Figures

Figure 1: LSHTM MSc Student Numbers 1998-2005

|

|

Learn more

about this

publishing

project...

|

|